Scientists Use Satellite Imagery to Count Elephants

The system helps conservationists monitor endangered species more closely.

Monitoring endangered species is vital to help them survive. In order to protect them from poachers or habitat destruction, conservationists need accurate monitoring.

Current methods are prone to error, which could lead to misunderstandings of animal trends and wrongly allocating resources. So a team of scientists from the University of Bath, the University of Oxford, and the University of Twente in the Netherlands, combined satellite imagery with deep learning to detect elephants from space.

Their study was published in late December in Remote Sensing in Ecology and Conservation.

SEE ALSO: AI HAS DISCOVERED NEARLY 2 BILLION TREES IN THE SAHARA DESERT

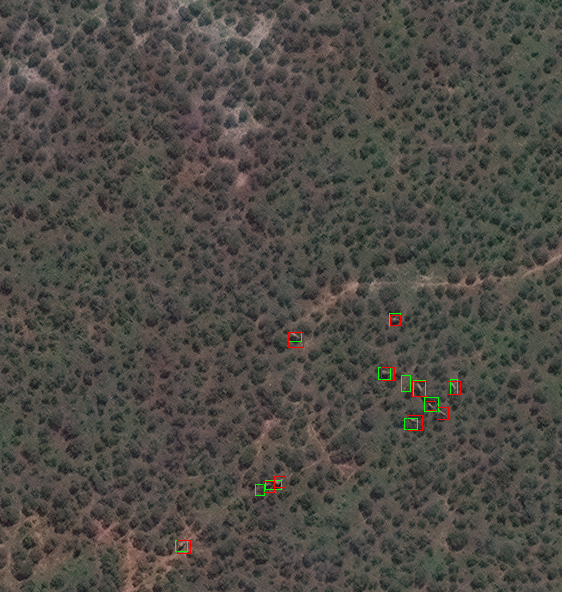

The team’s method proved comparable to human detection accuracy and could help solve a number of existing challenges, such as cross-border limits, and cloud coverage, among others.

The team used Maxar WorldView-3 satellite imagery, which is capable of collecting more than one million acres (5,000 km2) imagery in one go in just a few minutes. This allows for fast repeat imaging when necessary, and minimizes the risk of double counting as it’s so rapid.

Then the team leveraged deep learning to process the vast amount of imagery it collected from Maxar’s WorldView-3 satellite. In a matter of hours, the team collected its relevant data. This process usually takes months when sorting out by hand.

On top of speed, the deep learning algorithms also provided consistent results less prone to error, as well as false negatives and false positives.

In order to develop this method, the team created a customized training dataset of over 1,000 elephants, and then fed it into a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). After trials, the team concluded that its CNN can detect elephants in satellite imagery with as high an accuracy as human detection capabilities.

“Satellite imagery resolution increases every couple of years, and with every increase, we will be able to see smaller things in greater detail,” said Dr. Olga Isupova, a computer scientists at the University of Bath, adding: “Other researchers have managed to detect black albatross nests against snow. No doubt the contrast of black and white made it easier, but that doesn’t change the fact that an albatross nest is one-eleventh the size of an elephant.”

SHOW COMMENT ()

SHOW COMMENT ()